Gut–Brain Communication in Energy Homeostasis

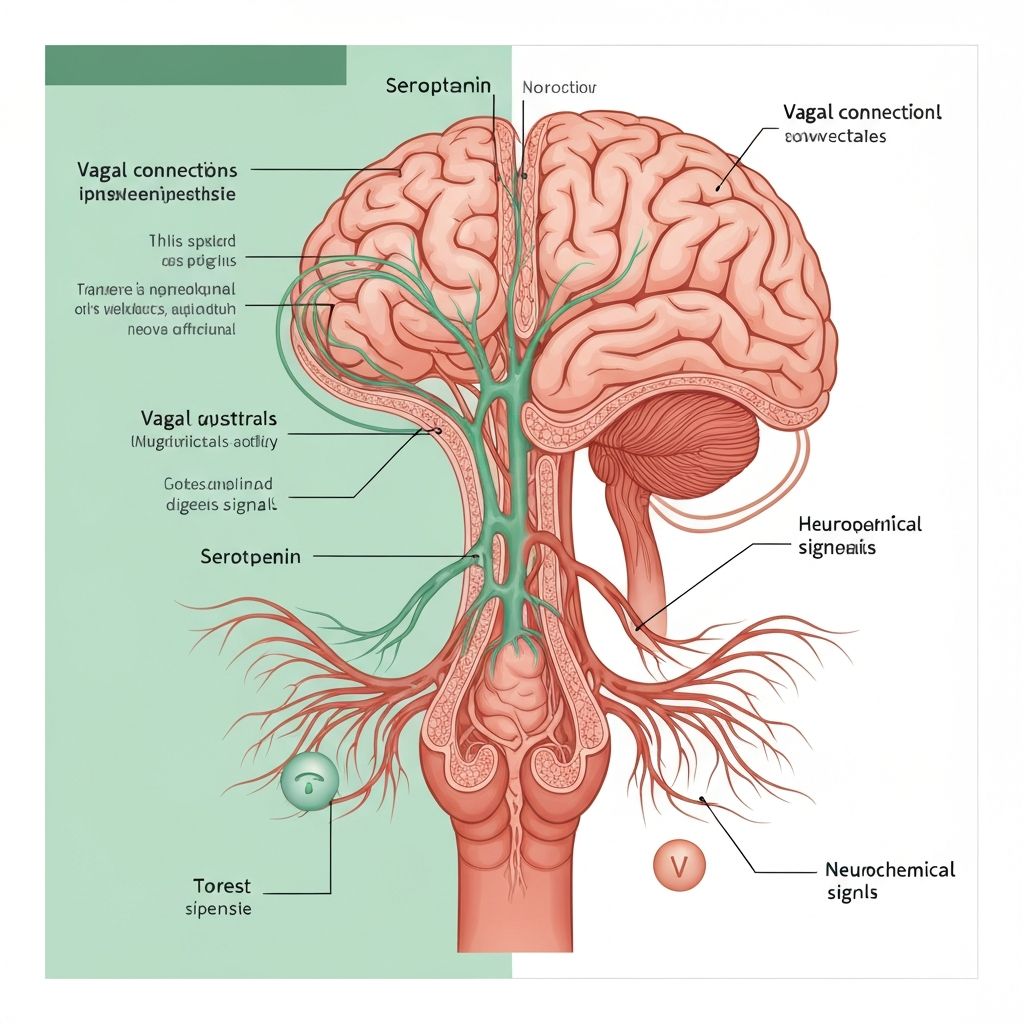

The gut–brain axis encompasses bidirectional signalling between the gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system, integrating microbial signals with host metabolic and behavioural processes. The microbiota influences this axis through metabolite production (particularly short-chain fatty acids), modulation of enteroendocrine cell function, and effects on intestinal immune responses. These signals are transduced to the brain through neural (vagal), hormonal, and immune pathways, influencing appetite regulation and energy balance.

The Vagus Nerve: Direct Neural Communication

The vagus nerve represents the primary neural connection between the gastrointestinal tract and brainstem. Vagal afferent nerve fibres originating from the nodose ganglion terminate in the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) within the brainstem, transmitting sensory information regarding gastrointestinal content, pH, osmolarity, and metabolite concentrations.

Enteric chemoreceptors and mechanoreceptors express receptors for microbial metabolites including SCFA receptors (GPR41, GPR43). SCFA binding to these receptors triggers neural signals transmitted via the vagus to the brainstem and subsequently to hypothalamic feeding centres. This pathway represents a direct mechanism through which bacterial fermentation activity and SCFA production influence central appetite regulation.

Experimental vagal ablation or anaesthesia impairs SCFA-mediated satiety signalling in animal models, demonstrating the necessity of vagal transmission for microbial metabolite-induced appetite suppression. This finding underscores the role of direct neural communication in conveying microbial metabolite signals to central appetite control regions.

Enteroendocrine Cell Signalling

Intestinal enteroendocrine L-cells distributed throughout the colon express SCFA receptors and respond to SCFA, particularly propionate and butyrate, by releasing glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY). These hormones circulate systemically and cross the blood-brain barrier, signalling satiety to hypothalamic feeding centres.

GLP-1 and PYY are powerful appetite suppressants; peripheral administration of these hormones reduces food intake and promotes weight loss in rodent obesity models and humans. SCFA-stimulated GLP-1 and PYY release represents a mechanistic pathway through which microbiota-derived metabolites directly suppress appetite.

Dysbiotic microbiota producing reduced SCFA concentrations impair GLP-1 and PYY secretion, potentially contributing to dysregulated satiety signalling and increased energy intake. Supporting this hypothesis, interventions restoring SCFA-producing bacteria or providing supplemental SCFA enhance GLP-1 and PYY secretion and promote satiety in experimental settings.

Hypothalamic Integration

The hypothalamus integrates signals regarding energy status through specialised neuronal populations in the lateral hypothalamus (promoting feeding) and ventromedial hypothalamus (promoting satiety). The paraventricular nucleus and dorsomedial hypothalamus coordinate these signals and regulate downstream neuroendocrine axes controlling appetite and metabolism.

Vagal afferent signals from SCFA-sensitive enteric neurons directly synapse within hypothalamic feeding centres. Peripherally released GLP-1 and PYY activate receptors on hypothalamic neurons, modulating feeding behaviour. Together, these pathways integrate gut metabolite signals into central appetite control.

Dysbiosis-associated reduction in SCFA production and enteroendocrine signalling results in attenuated satiety signalling to the hypothalamus, potentially promoting increased food intake and energy overconsumption. This mechanism is hypothesised to contribute to dysbiosis-associated weight gain, though direct human evidence remains limited.

The Microbiota-Derived Signals

Beyond SCFA, the microbiota produce numerous metabolites that influence brain function and appetite regulation. Secondary bile acid metabolites produced through bacterial bile acid metabolism modulate farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and Takeda G protein receptor 1 (TGR5) signalling, influencing energy expenditure and glucose homeostasis.

Tryptophan metabolites produced by the microbiota (kynurenine pathway metabolites, indole derivatives) influence aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) signalling, affecting intestinal barrier function and immune regulation. These metabolites may indirectly influence appetite through effects on intestinal health and immunity.

Dysbiotic microbiota producing altered metabolite profiles result in dysregulated signalling through these pathways, potentially contributing to metabolic dysfunction and weight dysregulation.

Systemic Inflammation and Appetite

Dysbiosis-associated systemic inflammation (through LPS translocation and pro-inflammatory cytokine production) can impair appetite signalling. Pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6 are known to reduce appetite and promote sickness behaviours. However, chronic systemic inflammation is also associated with dysregulated appetite, including paradoxical increased food intake despite systemic energy repletion—a phenomenon termed "inflammasome activation" or "metabolic endotoxemia-associated appetite dysregulation."

The relationship between systemic inflammation, appetite, and weight gain is complex and likely involves both acute appetite suppression and chronic adaptation with potential appetite dysregulation.

Neuroimaging Evidence

Human neuroimaging studies demonstrate that obese and dysbiotic individuals exhibit altered functional connectivity within hypothalamic feeding centres and prefrontal appetite control regions compared to lean, eubiotic controls. These alterations suggest structural or functional neural remodelling linked to long-term dysbiosis and altered metabolite signalling.

Whether these neural changes result from dysbiosis-associated metabolite dysregulation or reflect primary differences in brain structure predisposing to obesity remains unclear. Longitudinal studies tracking microbiota changes and neural remodelling during weight loss or gain would address this question.

Heterogeneity and Individual Variation

Interindividual variation in microbiota composition and metabolite production capacity underlies heterogeneity in appetite regulation and weight dynamics across individuals. Individuals with SCFA-producing-bacteria-rich microbiota may experience enhanced satiety signalling and better appetite regulation compared to those with dysbiotic microbiota. However, this variation is just one of numerous factors influencing appetite and weight regulation; genetic variation in appetite-regulating hormones, brain receptors, and metabolic pathways also substantially contribute.

Limitations and Unanswered Questions

Substantial evidence supports the role of microbiota-derived signals in appetite and energy regulation through multiple pathways. However, key questions remain unanswered. What quantitative changes in microbiota composition and SCFA production are necessary to produce physiologically meaningful changes in satiety and energy intake? Do dysbiotic microbiota-associated impairments in satiety signalling fully explain weight dysregulation, or are other mechanisms equally or more important?

Most mechanistic evidence derives from rodent models. Direct causal evidence in humans is limited, relying primarily on observational studies and short-term intervention trials. Long-term prospective studies tracking microbiota, metabolite production, appetite signalling, and weight dynamics in humans would substantially advance understanding of this complex system.